The Sentinel Project is building a network of like-minded stakeholders to collaborate on preventing and mitigating violence related to Kenya’s 2022 general election. Often seen as a beacon of stability in its region, political upheaval in Kenya can have ramifications throughout East Africa. Set against both a history of election violence and a background of many long-standing risk factors, the election currently scheduled for 9 August 2022 is also subject to several new elements which have increased the risk of conflict between various groups. While democratic elections are usually promising, during the general elections in 1992, 1997, 2007, and 2017, the country experienced heavy ethnopolitical violence that killed many people and displaced hundreds of thousands more. Many of the same underlying risk factors continue to be present while new exacerbating risk factors have now appeared. These include the following factors, which are explored in more detail below.

(1) Hate speech

(2) Prevalence of rumours and misinformation

(3) Devolved political competition

(4) Manipulation of youths

(5) Perceived political betrayal

The COVID-19 pandemic has also severely impacted Kenya’s economy and eroded progress in poverty reduction, forcing an estimated two million more Kenyans into poverty. When combined with increasing digitization and persistently low access to reliable information sources for many Kenyans, this political landscape will likely become more hazardous as harmful rumours and misinformation spread and further increase tensions and mistrust between different ethnic and political groups while hindering people’s ability to make sound decisions around the election. Our first blog post on this topic in March 2021 introduced some of the risk factors that increase the likelihood of election violence, including those that severely undermine trust in public institutions and the electoral process overall. This blog post provides an update on some of the most salient factors, which will be revisited in future assessments as election day approaches.

Hate speech

It has proven difficult to mitigate the spread and impact of online hate speech in Kenya, where electoral history shows how hate speech can incite conflict and inflict harm upon targeted individuals and communities. For example, political leaders instigated the country’s 2007-2008 post-election violence through hate speech circulated through various platforms such as radio, hate-related leaflets, and text messages. KASS FM radio presenter Joshua Arap Sang was indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for propagating hate speech against communities believed to oppose the party that he supported. This not only violated internal law but also the Kenyan constitution itself, which states in Article 33(2) that “The right of freedom of expression does not extend to propaganda for war, incitement to violence, hate speech or advocacy of hatred.” Section 13 of the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) Act adds that a person who propagates hate speech or incites ethnic hatred is liable to financial penalties and imprisonment of up to three years.

Despite the example of the ICC case and the existing Kenyan legislation banning hate speech, many reckless politicians continue to threaten instability with potentially inflammatory statements. Some have mastered the art of using coded language, emojis, vernacular, riddles, and proverbs to evade the law while still communicating hateful messages to their followers. Recently, the NCIC summoned Senator Franklin Linturi to explain the meaning of a word he used the Swahili word “madoadoa,” which refers to blemishes, to refer to unwanted people during a political rally in Uasin Gishu County, where many people lost their lives in the 2007-2008 violence. However, like many similar cases, the Linturi incident did not result in prosecution and the rampant use hate speech both online and offline continues to be of great concern. This is especially worrisome given Kenya’s high level of internet penetration and increasing use of social media platforms.

Prevalence of rumours and misinformation

The spread of harmful rumours and misinformation is an increasingly severe threat across Kenya as it destabilizes communities and increases the risk of violence, mainly in multi-ethnic counties. While there is increased recognition in the public health sector about the role of misinformation, a lot needs to be done in the peacebuilding sector to ensure that vulnerable populations are protected from consuming and spreading unverified information ahead of the elections. During the 2017 general election, opportunistic politicians and malicious actors took advantage of the information vacuum to disseminate false information that polarized citizens. For instance, in the Kibera and Mathare informal settlements of Nairobi, rumours circulated widely about armed members of the outlawed Mungiki criminal organization working with the police to target opposition supporters, which triggered panic across the city. This rumour diminished trust in the security forces and further complicated the ongoing peacebuilding and humanitarian efforts aimed at helping people who had been victims of violence. The preparedness of the Kenyan government and other stakeholders to tackle the menace of rumours and misinformation is still questionable at this time. To mitigate these risks, the Sentinel Project aims to expand its Una Hakika misinformation management project to 15 critical counties across Kenya, thereby engaging citizens in monitoring, verifying, and countering the spread of harmful rumours and misinformation in order to ensure that they can make decisions based upon accurate information.

Devolved political competition

Competition for political power and resources at the local level has intensified partly due to the devolved functions of government which shifted significant political power down from the national level when Kenyans voted to amend their constitution in 2010. Political antagonism is fundamentally identity based in Kenya, with ethnicity and clannism leading to fears of larger communities establishing hegemony. Counties such as Garissa and Tana River, where negotiated democracy, a traditional method of endorsing political leaders based on clan or tribe, is practiced, have previously experienced interclan and interethnic conflict due to constant accusations of impunity, selection of poor leaders, and battles for supremacy. Competition for grazing land, disputes over water points, and the presence of violent extremism have all exacerbated the problem.

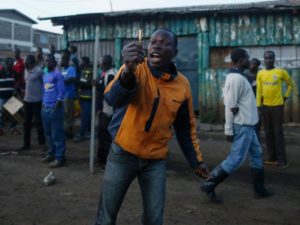

Manipulation of youths

Unemployment peaked in Kenya during the past two years, at least partially due to the pandemic’s economic impacts. This has rendered many youths vulnerable to political exploitation and manipulation. During previous elections, unscrupulous politicians hired youths to perpetrate violence against political opponents and allies. Youths form the majority of those who have done things like hurling stones at opponents, barricading roads, and vandalizing property. In the counties of Kisii, Murang’a, and Kirinyaga rival youths have engaged the police in running battles before and during political campaigns, killing several people leaving many with grave injuries. As Kenya prepares for the upcoming elections, such a level of intolerance breeds hatred and could potentially lead to widespread violence.

Perceived political betrayal

Dishonesty and betrayal are some commonly observed themes in Kenyan politics. Broken promises amongst coalition partners during the 2007 election is part of what led to the serious violence that followed it. Raila Odinga and his supporters accused President Mwai Kibaki of breaching the provisions of a memorandum of understanding that the parties entered into before the election. Kibaki’s move led to the unity of Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto that ultimately saw the Jubilee Party gain control of the presidency. History now seems to be repeating itself as Uhuru Kenyatta and his long-time political rival Raila Odinga have championed the Building Bridges Initiative and now the Azimio la Umoja Coalition. Deputy President William Ruto seems to have been sidelined and his close allies have accused the president of failing to fulfill his promise of supporting his deputy for the presidency in 2022 despite the latter maintaining his loyalty and allegiance to the president. They have also accused Odinga of intruding and destabilizing the Jubilee Party, which led to the formation of the United Democratic Alliance. Supporters of Odinga and Ruto, who are the critical contestants for the presidency, have already clashed at several campaign events.

———-

Past election-related clashes in Kenya have left hundreds of people dead, hundreds of thousands of others displaced, and both private and public property destroyed. The magnitude of the violence has torn Kenya’s social fabric and left behind ethnically-divided communities that continue to live in suspicion of each other. The election process in 2022 will be less contentious if there are mechanisms that help to stop the spread of harmful rumours and misinformation. At the same time, any violence that does occur will be less damaging if an effective early warning system is put in place to inform effective peacebuilding and violence mitigation initiatives at local levels. We now need other organizations, funding bodies, governments, and individuals to join our network and support these critical efforts. Click here to contribute to our ongoing fundraising efforts.