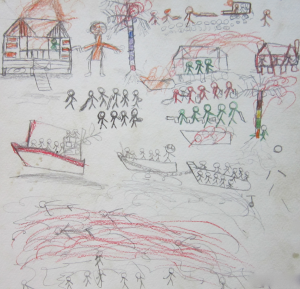

A drawing by a 9 year old boy from Kayauk Phyu depicts military robbing Rohyinga houses at gunpoint before burning them down and chasing those who tried to escape.

Among the most notable developments from Burma in March was news that Nobel-Prize winning Doctors Without Borders, commonly known by its French moniker Medicines Sans Frontiers (MSF), was removed from Burma. After media backlash, MSF was allowed to operate in Burma but not in Rakhine state, the locus of persecution and violence against the region’s Rohingya Muslims. The Burmese government accused MSF of “escalating tensions” and the “crime” of illegally employing Rohingya. The real motive, however, may hide sinister designs, particularly as the controversial census commences nation-wide.

Tensions had been rising since MSF contradicted the Burmese government in mid January when the regime claimed no Muslims had been killed in a pogrom near Maung Daw, in Duchiridan village. MSF attested to treating multiple casualties and the United Nations found that dozens had been killed, both reports frustrating government attempts at a cover-up. According to one ex-humanitarian aid worker, the move was aimed at eliminating witnesses. “MSF was targeted for expulsion soon after June 2012 violence,” she said in an interview conducted by the Sentinel Project. “MSF’s statement about treating victims of violence near Duchiridan Village, Maungdaw Township soon after the reported mass violence in mid-January was a rare public statement but enough to be the last straw for the military political ruling machine.”

This was not the first time MSF had been a gadfly of the state in Burma. The organization has at times, not deliberately, exposed systemic abuses against Rohingya and contradicted official accounts of the conflict in Rakhine state. In its official capacity, MSF has found that officially-imposed government limitations on Rohingya, particularly restrictions on movement and imposed squalid living conditions, have placed thousands in unnecessary medical peril and that displaced persons’ camps worsen periodic violence. Because of the inflicted nature of Rohingya suffering, MSF’s public healthcare advocacy has been problematic for a government attempting to carry out appalling crimes in secret. Aid organizations merely attempting to help those in need have been a persistent and festering thorn in the side of a regime claiming to have reformed while still retaining its grip on power.

On March 27, crowds rampaged through the streets of Sittwe, attacking offices of other foreign-aid organizations. Despite their mission to provide medical aid without ideology and bias, MSF members have been attacked physically, on the internet, and in the local media. In Burma, MSF has historically been the target of threats and intimidation by a small but vocal minority seeking the expulsion or annihilation of the Rohingya. Last February, the aid organization released a statement detailing attacks on social media and in pamphlets and letters. “One community leader recently described MSF’s medical aid to displaced persons outside their village as watering a plant, a plant he does not want to see watered,” noted the report. [1]

The Sentinel Project’s ThreatWiki noted intimidation on social media in August 2013 as well, specifically directed at Doctor’s Without Borders. In November, the organization was forced to suspend their operations in Sittwe because of allegations, later revealed to be untrue, that they had denied medical services to ethnic Rakhines.

Burma has now eliminated MSF in the westernmost state of Burma, a credible eyewitness and source of information about the local and national authorities’ activities. Clearing the area of potential witnesses to genocide may be an attempt to hide crimes against humanity and shield the perpetrators from justice. According to the Sentinel Project’s humanitarian contact, this practice is not new, but a broadening and deepening of policies to limit the spread of information: “Myanmar’s ruling military political party in control before and after the 2010-12 transition from Military Dictatorship to Civilian Parliamentary System always restricted international witnessing and access to areas in which national security forces have been conducting military, brutal persecutory, and regime development projects.”

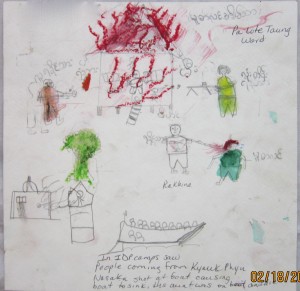

A drawing by a 12 year old boy from Pa Lote Taung Ward shows soldiers shooting at boats full of Rohingya, all of whom died.

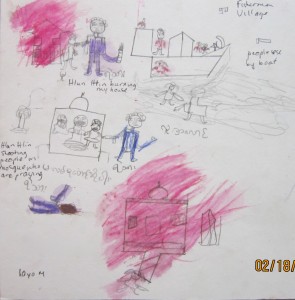

A drawing by a 13 year old boy showing Hlun Htaine (security police) shooting Muslims with machine guns.

A drawing by a 10 year old boy depicts Hlun Htaine (security forces) burning the boy’s house and firing into a Mosque with a machine gun.

[1] http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/article/ongoing-humanitarian-emergency-myanmars-rakhine-state