Recent analysis conducted for the London Conference on the Destruction of Myanmar’s Rohingya held at the London School of Economics in late April showed that violence often characterized as “communal” by many media outlets is in fact government planned and coordinated.

The History of Sentinel Project Mapping in Burma:

In the spring of 2013, the Sentinel Project began mapping acts of persecution against the Rohingya, specifically those acts that fit Gregory Stanton’s Eight (now Ten) Stages of Genocide, in order to better understand the unfolding situation in Rakhine State and greater Burma. The project expanded on the previous success the Sentinel Project had had mapping incidents involving the Bahai community in Iran and identifying regions at particular risk for known precursors to genocide.

As with any living document, the results of mapping with ThreatWiki are always changing and conclusions, successes, and weaknesses are evolving. The Burma Team initially envisaged three goals for the employment of GIS technology in Burma: to provide early warning and predictive intelligence, to identify the roles of organizations and degree of responsibility of the Burmese government, and to provide scientific advice for NGOs and government agencies on how to best approach any identified mitigation of, or long-term solution to, the current crisis.

Why GIS?

Geospatial information systems or GIS is more than just the placing events or ideas on a map; it has a track-record of inspiring and informing solutions to complex social issues, even violence-prevention.

In the early 1990s, as the Soviet Union and its satellite states broke apart among ethnic and national lines, the diverse regions of the former Yugoslavia became killing fields. The Balkans were the crucible of the unprecedented violence of the 20th century – as Gavrilo Princip, a man who became a catalyst for the carnage of the First World War and its aftermath, said in 1914 “I am a Yugoslav Nationalist. I call for the reunification of the Southern Slavs into one state.” Almost 80 years later, in Bosnia-Herzegovina, a state made up of Croatians, Serbs, and Muslims rekindled extreme nationalism and became embroiled in ethnic cleansing and genocide for the first time in Europe since 1945.

Not wanting to repeat the errors of the various treaties that escalated tensions in Europe after World War I, the Dayton Accords was to be an exercise in statistical and scientific boundary-drawing, attempting to prevent violence through informed geographical decisions. Signed at the end of 1995, the Dayton Accords marked the first use of geospatial digital technology in diplomatic negotiations. It allowed state leaders and all stake-holders to be informed and their concerns minimized through visual demonstration of proposed boundaries in PowerScene. Since the Bosnian Genocide, GIS has played an increasing role in international conflict revolution, domestic policy making, and in the private sector as well.

Using GIS to Predict Persecution in Burma

When violence erupted in Lashio, the capital in Myanmar’s northern Shan state, many were shocked because it had, to that point, been spared from violence between Buddhists and Muslims and it was far from Rakhine State, the uncontested locus of anti-Muslim and anti-Rohingya campaigns. Lashio was also notable because it was one instance where the local Buddhist population rushed to help Muslims escape the mobs who were permitted to conduct ethnic cleansing operations for two days before security forces acted against them.

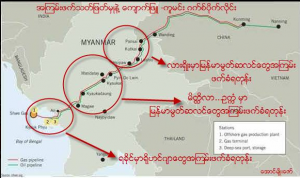

Illustration 2: Map Showing gas and oil pipelines and violence against minorities (Facebook: source unknown).

Illustration 1: 2 Days of Violence in Lashio, Shan State illustrated by ThreatWiki

Without GIS, Lashio would merely be an anomaly, without any plausible explanation. However, a map which surfaced on social media (Facebook: source unknown) purported to show a correlation between Burma’s controversial Shwe oil pipeline and incidences of violence against ethnic minorities. Not only had the Burmese government been embroiled in battles over land-seizures from farmers to make way for the pipeline, often resulting in violence, the government had also polarized local populations, turning them against each other as a means of distraction. Lashio fit with this national policy perfectly. The pipeline bifurcates the Northern Shan and Southern Kachin regions, regions in which ethnic minorities had been in open armed conflict with Burma’s central government for decades. Along the path of the pipeline lay several locales where human rights violations, lynchings, massacres and ethnic cleansing campaigns have been carried out including Naung Cho, Meiktila, Magwe, and Sittwe. This was some of the earliest evidence that the most recent outbreaks of violence in Burma were not, as many characterize them, local, popular, and communal, but rather government-supported and sponsored.

GIS has been helpful in vetting intelligence about future actions against the Rohingya, but not predicting them at a greater accuracy than population concentration would indicate. It is only common sense that areas with a higher concentration of Rohingya tend to have more outbreaks of violence. The organized nature of violence is also supported by the tempo of incidences. If the ethnic cleansing campaigns were communal in nature, one would expect a variety of small incidences building up to outbreaks of mass violence and atrocities; however, in Rakhine State and greater Burma just the opposite is true. Many outbreaks of mas violence appear spontaneous, prompted by one incident involving a Rakhine and a Muslim. The January 2014 violence in Durchiradan (Kila Dong), for example, followed a relative period of calm according to ThreatWiki. Many residents of these outbreaks of violence were shocked because they had previously lived peacefully with local Rakhines. The same was true in late October 2013 when more than 400 Muslim shops were burned in Northern Maung Daw and in Lashio in May. The best predictor for violence, instead, was human intelligence garnered through social media, which by its nature often lacks in credibility and which requires vetting, something that ThreatWiki can contribute to but is not sufficient in itself in the event of centrally organized pre-planned violence.

GIS and the Degree of Government Involvement in Ethnic Cleansing and Atrocities

Until Matthew Smith of Fortify Rights revealed leaked documents detailing official government policies of anti-Rohingya persecution in February 2014, the Burmese government hotly denied any policies that would be regarded legally as genocide, casting the outbreaks of violence as the price of emerging liberty and communal sentiments toward Muslims.

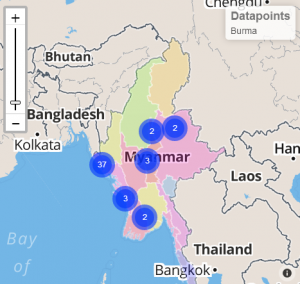

The ThreatWiki database on Burma had since its development included tags to characterize whether incidences involved government personnel or security force abuses. Out of all the datapoints representing incidences of persecution against Rohingya, slightly more than 56% involved Security Forces Abuses. This included sexual assault, extortion, beatings, arrests, torture, and even murder of Rohingya. More than 12% of all incidences had some link to local or national government. When considered as a whole, then, nearly 70% of all incidences were openly linked to elements of the Burmese state, whether regional or national in nature. This data not only contradicts the official version of events proffered by Burma’s government, but also refutes the characterization of violence as communal by many media outlets.

Illustration 3: ThreatWiki map showing Security Forces’ abuses involving Muslims, a phenomenon widespread in Burma.

Using GIS to Support Aid to Rohingya

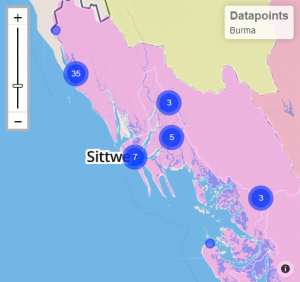

While the advanced stage of genocide against the Rohingya would indicate drastic measures are needed, up to and including evacuation and even self-defence, some agencies are still needed to provide emergency aid including food, medicine, and shelter. Mapping with GIS has proven instrumental in unofficial communities in the past. In Kenya, for example, the mapping of the Kibera slum in Nairobi resulted in better access to essential services and a marked increase in safety and security for its residents. This experience in mapping in communities which a government deems unrecognized, unwanted, and illegitimate, can be critical in the long term. In the slow genocide of Burmese IDP camps, GIS could provide real assistance to makeshift communities, especially as they grow in size.

In the fall of 2013, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) contacted the Sentinel Project. They wanted more information on the development of the Sentinel Project’s GIS monitoring feature, ThreatWiki. As a mark of the rising importance of mapping and GIS, USAID employs its own GIS analysts. Mapping analysts are allowing government aid agencies to deliver more for less, targeting small dispersals of cash in the areas where they are most needed and in the manner which is most effective.

Illustration 4: ThreatWiki shows aid most needed in northwestern Rakhine state.

The Sentinel Project put USAID in contact with Richard Potter, a social-worker and activist from Pittsburgh, PA involved in the UK-based “Save the Rohingya” campaign, who had a rather unique idea with a lot of potential. Potter is working on a plan to install blacknets, or small, inexpensive, wireless networks into IDP camps and other areas where the potential for persecution and violence is high and government blockades prevent the flow of information. Emerging commercial technology like the RaspberryPi can be set up covertly, made robust and durable, and be powered by solar energy. In a state with little access to electricity and where internet connectivity is less than 1%, blacknets could have revolutionary potential. These networks could provide channels on which information could flow out of areas blacked out by the Burmese government to hide atrocities. Information could bypass government censorship and security forces, and provide a useful lifeline out of isolated and guarded camps. The idea is that information could be the key to pressuring Burma’s authorities to ease restrictions and could ultimately provide evidence for future trials for crimes against humanity under international law. GIS can provide data on where blacknets are most needed and likely to be most effective.

Mapping is not a solution on its own, but a tool to support and inform policy. With proper funding and staffing, GIS can have a huge impact on mitigating and preventing violence through early warning, vetting of human intelligence, and targeting aid. The small gains the Sentinel Project and tools like ThreatWiki have made may seem wholly inadequate compared to the great threats the Rohingya face in Burma, but what has been accomplished: the raising of media awareness, the informing of governmental foreign policy, and the promise of future projects, cannot be discounted. As Turkish author Mehmet Murat Ildan writes: “Without water drops, there can be no oceans; without steps, there can be no stairs; without little things, there can be no big things!”