Over a million Rohingya refugees currently live in the Cox’s Bazaar region of Bangladesh. Although Rohingya people have fled into Bangladesh due to state-sanctioned genocide in Myanmar since the 1970s, the largest and latest exodus began in August 2017, when 742,000 people were forced to flee life-threatening violence, and seek refuge over the country’s border.

Citing issues of overcrowding, congestion, and security in Cox’s Bazaar, since October 2017, the government of Bangladesh has been developing a relocation site for 100 000 Rohingya refugees. The Bangladeshi government has overseen the construction of concrete housing structures, flood defense embankments, cyclone shelters, prefabricated food and storage warehouses, roads, and a solar power grid. As a 2018 Reuters article details, a Chinese construction company, Sinohydro, has worked on a flood-defense embankment and HR Wallingford, a British engineering and environmental hydraulics consultancy, is advising the project on “coastal stabilization and flood protection measures.”

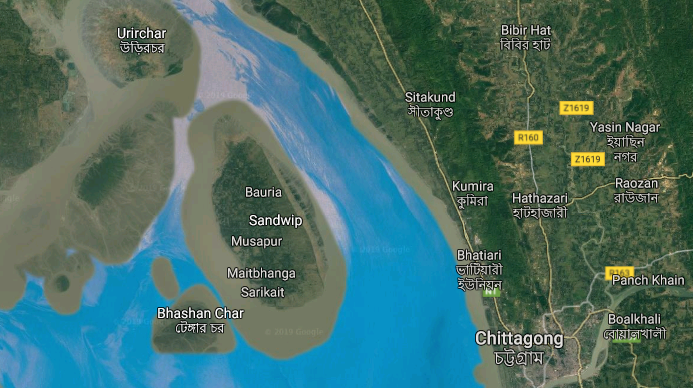

However, the relocation site is situated on an island hundreds of kilometres away from the current camps in the Bay of Bengal, at the south end of the Meghna River. Known as Bhasan Char or “floating island,” it is a flat and uninhabited piece of land formed 20 years ago by moving silt (CBC, 2019). The landmass emerged as one of the many shifting islands, or ‘chars’ that naturally occur in the region. Located 30 kilometres off of the coast, it is estimated to be a three-hour boat ride from the mainland of Bangladesh.

Several key concerns have been raised by observers regarding the relocation plan. First, the island is prone to natural disasters such as flooding and cyclones. In August 2018, Bill Frelick, Director of the Human Rights Watch (HRW) Refugee Rights Program stated that “Bhasan Char is not sustainable for human habitation and could be seriously affected by rising sea levels and storm surges.” More recently, in January 2019, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Yanghee Lee, visited Bhasan Char Island with Bangladeshi officials. In the press conference following her visit to the island, Lee called on the Bangladeshi government to “share the feasibility studies it has undertaken and to allow the UN to carry out a full technical and humanitarian assessment, including a security assessment, before making any further plans of relocation to the island.” She noted, “There are a number of things that remain unknown to me even following my visit, chief among them being whether the island is truly habitable.”

Second, questions surrounding access to basic services, such as education and health services, and livelihoods remain unanswered. The enforcement of the right to freedom of movement is also under scrutiny. Bill Frelick further noted in the same article that the island would “most likely would have very limited access to education and health services, and extremely limited opportunities for livelihoods or self-sufficiency.” As the Asia Director of HRW, Brad Adams also stated that “Dumping a battered and traumatized people on Bhasan Char to face yet another threat to their survival is not a solution. Bangladesh should terminate the relocation plans unless or until independent experts determine that the island is suitable, and until the government ensures that refugees who consent to relocate there will be allowed freedom of movement on and off the island.”

Third, there are concerns around information-sharing, communication, informed consent, and the (in)voluntary nature of relocation. Starting in November 2019, the plan was supposed to begin with Rohingya families who have signed up voluntarily for relocation. However, the government announced a temporary halt in the relocation plans on 3 November 2019. On 12 November 2019, 39 non-governmental organizations from around the world signed an open letter to the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina Wazed, welcoming the pause in plans. The letter underlined that in event of future relocation plans, Rohingyas need to be sufficiently informed and consulted before any decisions are made, and relocation must not happen without their informed consent and free will. The letter mentioned that many Rohingya refugees living in the camps in Cox’s Bazar are understandably wary and fearful, and are in opposition to the move. As Matthew Smith of Fortify Rights, in writing about the open letter noted, “The island is not a sustainable solution for refugees and no one knows that better than the Rohingya themselves…Threats of forced relocation cause unnecessary harm to refugee families already struggling to survive. Bangladesh authorities should engage in meaningful consultations with Rohingya and identify options to ensure rights and protection.”

As a hopeful step, The Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief Senior Secretary Shah Kamal announced that the government would allow the UN to conduct a technical assessment of Bhasan Char island from 17-19 November 2019. And luckily, immediate plans to move people have been postponed, and international media attention has died down. However, as these three key concerns loom, the future viability of Bhasan Char is still to be determined.