Dr. Kjell Anderson is a member of the Council of Advisors for the Sentinel Project. Additionally, he is a lecturer and researcher at the Netherlands Institute for War, Holocaust, and Genocide Studies (NIOD). This commentary is partly based on research conducted for a forthcoming work of fiction on the life of Buddha.

Introduction

The violence directed at the Muslim minority in Burma over the past several years is often characterised as sectarian conflict or genocide between Buddhists and Muslims; yet we must not accept this notion uncritically. The ways through which we describe and characterise violence have fundamental implications for the development of appropriate policy responses. In this four-part series I will investigate the violence in Burma through several interpretive lenses. In Part One I will examine the ethnic and religious dimensions of the violence. Is the violence rooted in religious extremism and sectarian tensions, or is there something else at play? In Part Two I will examine the nature of hate speech in Burma, while Parts Three and Four will broaden the analysis to consider the mobilisation of violence and the legal classification of mass violence in Burma. In particular, I will raise the question of whether we are witnessing genocide or sectarian riots. Through this analysis I hope to provide an interpretative lens for understanding violence in Burma.

The infallibility inherent in religious belief is also the apparent great failing of religions. Religiosity, critics argue, inflames believers with self-righteous ire seeking to proselytise or destroy all non-believers. In this conceptualisation religion is poison, as Mao Zedong famously said. It is a cause of violence and even of genocide. There are certainly historical precedents which seem to support this claim: from the persecution of the Knights Templar to the Spanish Inquisition. However, as the case of Burma illustrates, so-called religious violence often contains multiple irreligious dimensions.

Typical narratives describing the recent anti-Muslim violence in Burma seem to fall into one of two categories: the “Rohingya genocide” or “religious riots.” Each of these characterisations is misleading. We are actually speaking about two separate, but related phenomena which have occurred, most recently, in Burma from 2012 until the present: violence targeting the Rohingya Muslim minority in Rakhine state and violence involving Burmese Muslims more generally. In this blog post I will discuss the anti-Muslim violence in Burma from the perspective of religious belief (truth) and politicised ethnicity (tribe). I will touch on the close relationship between religious and ethnic identity, as well as questioning the Buddhist doctrinal basis for violence in Burma, and the roots of so-called Buddhist nationalism.

Religion and the Rise of ‘Buddhist’ Nationalism

Religion and ethnicity are often inseparable. Religious identity is one of the markers of difference which defines ethnicity. Indeed, religion is a fundamental aspect of how we see ourselves – beyond being a system of personal belief it is also shared belief, which binds us to other members of the same religious group. There are many examples of interlinked ethnic and religious identity. Moluka islanders in Indonesia are both ethnically distinct from Javanese, as well as religiously distinct (they are largely Christian, whereas most Indonesians are Muslim). Sri Lanka is another example of the confluence between religious and ethnic nationalism. Tamils are both ethnically distinct from Sinhalese as well as religiously different (they are primarily Hindus, whereas most Sinhalese are Buddhists). Religion can actually have the effect of reinforcing ethnic nationalisms by creating another element of distinction between ethnicities. Indeed, religious identity can heighten ethnic nationalism by rendering outsiders as not only culturally different but heretical.

In Rakhine state in northwestern Burma the Rohingya are both ethnically and religiously distinct from other Burmese.[1] They are predominately Muslim and said to have migrated from Bengal during the reign of King Narameikhla (1430–1434). In total Muslims represent 4% of Burma’s population, according to official government statistics. Beyond the Rohingya in Rakhine these Muslims live throughout Burma and originate from diverse sources such as Persia, China, India, Arabia, and Malaysia.

Burmese policies have long discriminated against the Muslim minority, particularly the Rohingya. This dates back to pre-colonial times where policies prohibited halal slaughter and the observance of Islamic festivals. There have been several recent outbreaks of violence targeting Muslims, such as in 1977-1978 when 200,000 Muslims fled Rahkine to escape persecution, and again in 1997 when anti-Muslim violence in Mandalay resulted in several deaths. In the past three years episodic violence in Rakhine, Mandalay, and elsewhere which has resulted in the forced displacement of hundreds of thousands of Muslims and hundreds of deaths.

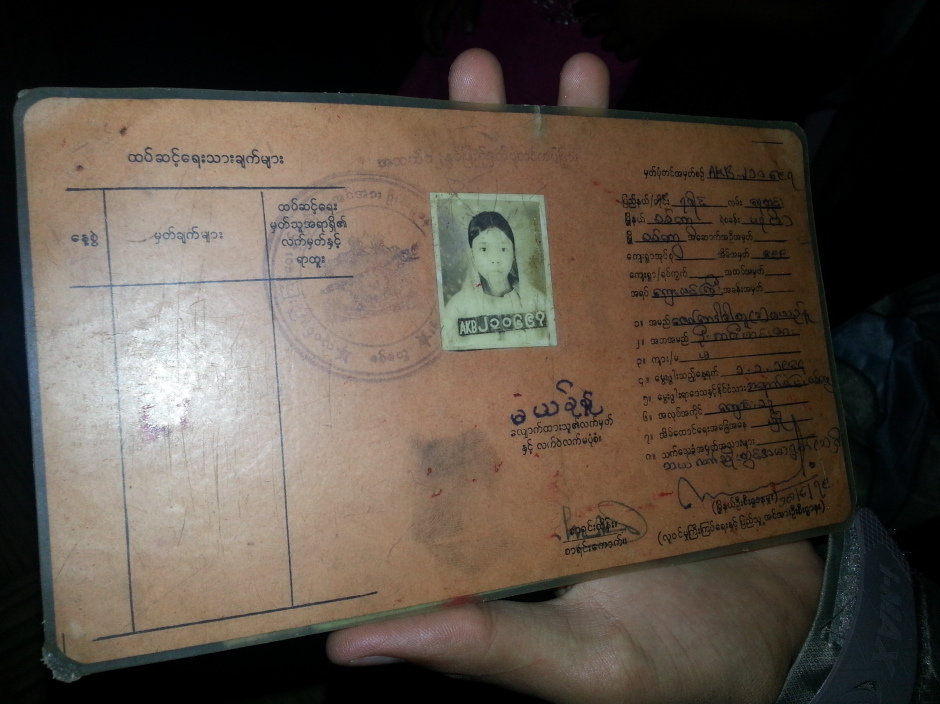

The Burmese government denies the existence of the Rohingya as an ethnic minority, instead labeling them as “Bengalis.”[2] Moreover, all Rohingya must prove that they arrived no later than 1823 (the beginning of British occupation in Rakhine state) in order to be eligible for Burmese citizenship. The framing of Rohingya as Bengali is an attempt to “other” them, denying their legitimate roots in Burma. The recently announced Rakhine State Action Plan refers to Rohingya only as “Bengalis” and marginalises those Rohingya who are denied citizenship by forcing them into isolated and restrictive resettlement zones.

The violence has been led by a Buddhist nationalist group called the 969 Movement, which rose to prominence after the release of nationalist activist monk Ashin Wirathu from prison in 2012. The name of the group arises from the 9 special attributes of Buddha, the 6 special attributes of the Dharma (Buddhist teachings), and the 9 special attributes of the Sangha (Buddhist monastic community). Collectively these three elements (Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha) form the “three jewels” – the core of Buddhism. Beyond numerology the selection of the name 969 is also rooted in Islamophobia. Many businesses throughout South Asia display the number 786 (a reference to the Koran) to indicate that they are Muslim-owned. The 969 movement directly plays off fears of Islamic dominance.

As with many genocidal movements the roots of the prejudice against Burmese Muslims is rooted partly in notions of cultural difference but, more fundamentally, in the notion that Muslims are foreigners who do not belong. Moreover, there is a sense that Islam, as a religion, is fundamentally expansionist. Nationalist discourse often raises the spectre of a creeping Islamicisation of Burma. Paradoxically this fear seems also to be rooted in a sense of inferiority; like the Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) movement in India there is a sense that Muslims are tougher and more united than Buddhists. This ‘backhanded compliment’ contains the essence of the threat of Islam. As Wirathu stated: “You can be full of kindness and love, but you cannot sleep next to a mad dog…If we are weak, our land will become Muslim.”[3]

The incitement to violence against Muslims, led by nationalist elements including some Burmese Buddhist monks, feeds on this fear. The discourse goes that Muslims seek to suborn Buddhism and to impose an alien and heretical doctrine on all aspects of life in Burma. Let us now further examine the Buddhist dimensions of violence in Burma.

Buddhism and Violence in Burma

“…and because of defensiveness, various evil unwholesome things originate – the taking up of clubs and weapons, conflicts, quarrels, and disputes, insults, slander, and falsehood.” – Mahānidāna Sutra

Buddhism has a reputation of being a religion of peace; how then can Burmese Buddhist monks be playing a role in inciting violence in Burma? In order to answer this question we must first note that Buddhist theology is vast and pluralistic, in the sense that there is not Buddhist equivalent of the Bible or the Koran – rather there are innumerable religious texts in the Buddhist canon. Moreover, the manner in which Buddhism is practiced is dictated at least partly by geography – Buddhist beliefs often meld to local cultural contexts. In this sense it is more accurate to speak of “Buddhisms” rather than a single, unified Buddhism. Indeed, there are few Buddhist doctrines which are universally held in Buddhism beyond the Four Noble Truths.[4]

Nonetheless, something of the essential essence of Buddhism can be derived from the life of Buddha himself, particularly as reflected in the Pāli canon (the earliest Buddhist sutras). Buddha’s outlook was fundamentally moderate. His creation of the so-called Middle Path was a solution to what he saw as the extremes of, firstly, extreme hedonism, and secondly, extreme asceticism. Buddha grew up in this hedonistic world as a royal prince denied any knowledge or experience of suffering. After he fled the royal place he sought spiritual awakening through extreme self-mortification and study with various ascetic teachers until he had the realisation that extreme asceticism was itself an impediment to the clarity of mind required for enlightenment.

Buddha spoke repeatedly of the necessity of ahimsa (non-violence) and demonstrated his commitment to this principle on several occasions such as in the fable of Angulimāla, in which he stops a serial killer by showing him the error of his ways, and the Jātaka rebirth tales, which often contain a non-violent message. One of his ten “disciples,” Mahākaccāna, even touched on the issue of sectarian conflict saying, in response to a question as to why ascetics fight with ascetics: “It is, Brahmin, because of attachment to views, adherence to views, fixation on views, addiction to views, obsession with views, holding firmly to views that ascetics fight with ascetics” (Aṅguttaranikāya Sutra). Even during his lifetime Buddha experienced this fixation on views, as a schism within his Sangha, when his cousin Devadatta formed his own community as a response to what he saw as Guatanma Buddha’s lack of discipline.

There were no incidents in the life of Buddha where he encouraged or abetted violence. Arguably Gautama Buddha was himself a survivor of genocide with the destruction of his kin (the Śākyas) in his lifetime.

Yet in spite of the rootedness of Buddhism in non-violence and moderation, Buddhism, like all religions, has also been used as a justification for violence. Buddha himself came from a warrior caste and was connected to political structures which sometimes used violent force. Moreover, there are further examples of “Buddhist” connections to violence in the warrior Zen of medieval Japan and the sermons given to the Sri Lankan army by Buddhist monks.[5]

In Buddhist ethics intentionality is paramount and violence may be justifiable only as an act of compassion (controversially the Treatise on the Great Vehicle recounts a story of killing Brahmans out of compassion in order to stop them from committing heresy, thus earning an unfortunate rebirth). It seems impossible to argue that the intentions of Buddhists in Burma who participate or incite violence against Muslims are rooted in compassion, therefore these acts must be incorrect according to Buddhist ethical principles.

The Dalai Lama, the most famous Buddhist figure in the world and the leader of most Tibetan Buddhists, condemned anti-Muslim violence in both Burma and Sri Lanka in 2013 saying: “Really, killing people in the name of religion is unthinkable, very sad,” and encouraging monks to “picture the face of Buddha” before they commit acts of violence. Nonetheless the Sri Lankan Sinhalese nationalist monk Galagodaatte Gnanasara responded angrily to the Dalai Lama’s comments arguing that he does not represent all Buddhists and that he was ignorant of the “true situation in Sri Lanka” and was a victim of “Islamic extremist propaganda.”[6]

Buddhism, like other religions, seems to be most likely to be used as a justification for violence when married with state power. The state will draw from whatever doctrine it deems suitable, and even rewrite that doctrine, in order to provide higher justification for its own acts of violence. Consequently one may question how close religious leaders should be to state power. Buddha himself advised the king of Kosala, and the Dalai Lama, until 2011, held both secular and religious authority over Tibetans. This tension between religious piety and secular duty is also represented in Buddhist writings in the form of the foretelling by the prophet Asita that Buddha would be either a great ascetic or a world-ruler (cakkavatti). Buddha’s father, Suddhodana, desiring greatly for his son to be a lord of the secular world, rather than live the life of an isolated ascetic, attempted to shelter him completely. In the end, of course, Buddha chose to follow a religious path.

Conclusion: Truth and Tribe

So how, then, should we characterise the violence in Burma? Who are the perpetrators: are they Buddhists or Burmese? Are the victims Muslims or Rohingya? There are no simple answers. The perpetrators of the violence are both Burmese and Buddhist and the victims are both Muslim and (often) Rohingya. The violence, in some sense, is both ethnic and religious, although it appears not to be grounded in any religious ideology. Religion, in this case, would seem to be more of a marker of ethnic identity than an identity in and of itself. While the perpetrators happen to be Buddhist it is difficult to say that it is ‘Buddhist violence;” Egyptian clerics recently objected to the label “Islamic State” for similar reasons: this group’s recourse to violence is not rooted in religious doctrine. It must, of course, also be noted that ethnic identity is not an inherent source of conflict. Rather, it is the politicisation of ethnicity, often grounded in prejudice and entrepreneurial leadership, which can lead to conflict.

Religion appears to be most dangerous when it becomes a marker of exclusionary collective identity, rather than a set of personal beliefs. Adopting or maintaining religious belief is almost always an act of identity affirmation, alongside the absorption of doctrinal notions. Religion is culturally-bounded: paradoxically, the culturally-situated practice of religion may sometimes serve to undermine the source material. For example, one could argue that the assertion of religious identity, as an act of building personal identity, is also contradictory to the core Buddhist teaching to extinguish the self (anattā). Consequently it would appear that the ethno-nationalism of the 969 movement is entirely irreligious.

Most religions reject violence, yet violence often occurs in the name of religion. The key to ending this trap seems to be to emphasize universalist notions of empathy and compassion for others over any notion of doctrinal certainty. Perhaps, religions might also benefit from an infusion of values from the ‘secular religion’ of human rights.

Part Two of this series will analyse anti-Muslim hate speech in Burma.

[1] Although the Rohingya are a majority within Rakhine state they are a minority within Burma.

[2] The Rohingya are sometimes also referred to by the racial slur “kalar.” See HateBase: http://www.hatebase.org/vocabulary/kalar.

[3] http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/wp/2013/06/21/i-am-proud-to-be-called-a-radical-buddhist-more-burmese-buddhists-embracing-anti-muslim-violence/

[4] The four noble truths were dictated by Buddha in his first speech to his followers in Deer Park. These truths can be summarised as follows: there is suffering, suffering has an origin, suffering can cease, and there is a path to the cessation of suffering.

[5] See, for example, the work Buddhist Warfare edited by Michael K. Jerryson and Mark Juergensmeyer (New York: Oxford, 2010).

[6] http://www.straitstimes.com/news/asia/south-asia/story/sri-lankas-militant-monk-rejects-dalai-lama-spiritual-leader-20140722.