Kenya is a deeply divided country with a history of ethnic rivalry and antagonism. It once enjoyed relative peace and stability but the recent transition to democracy has seen episodes of large scale violence as different groups compete for power. Unless addressed effectively, this situation is likely to produce further unrest that could escalate into genocide.

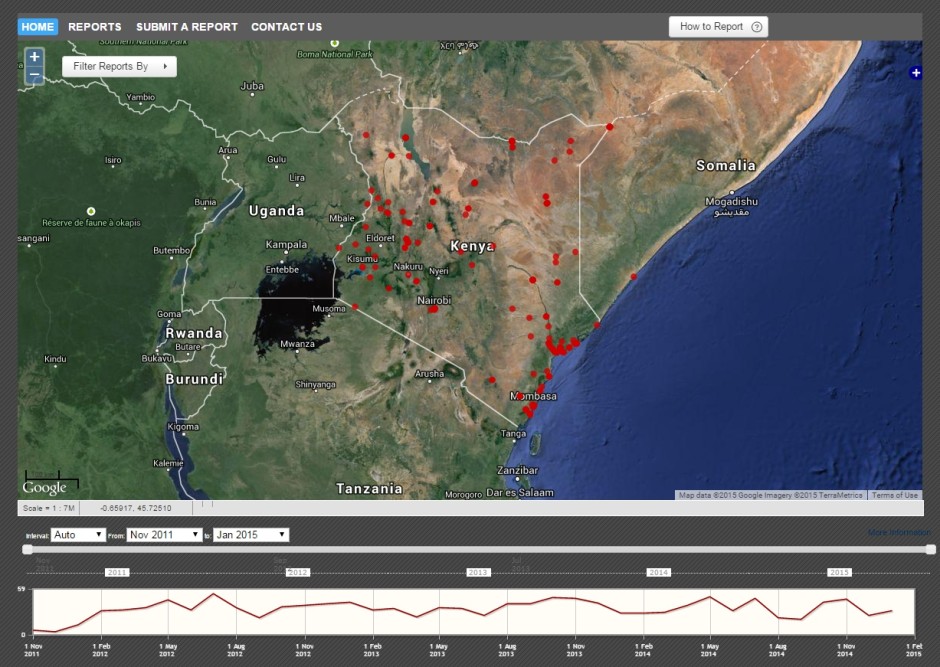

Operational Process Monitoring

Operational Process Monitoring is a continuous process of tracking events in an situation of concern (SOC) to identify event patterns and key actors involved. Events are classified according to the Operational Process model, which defines nine processes that underlie every historical instance of genocide. These processes, defined in detail in the section Stages of Genocide Model, all contribute to planning or implementing genocide.

You have access to the data visualization of the events logged in our Sentinel Conflict Tracking System by our Kenya Research Team. You are able to visualize on a map the different events, at specific time and classified by tags.

Background Information

In November 2012, the Sentinel Project released a comprehensive risk assessment report for Kenya. This report is available for download here, and the executive summary is include below.

Download the report: Risk Assessment – Kenya 2012 (PDF)

The risk of Genocide in Kenya

The Sentinel Project for Genocide Prevention has conducted a comprehensive assessment of the risk of genocide in Kenya and found that risk to be high. Analysis of various aspects of Kenyan society, including political, social, cultural, and economic characteristics, indicates that many factors which have been identified as potential precursors to genocide are present in Kenya. This does not indicate that genocide is inevitable in Kenya, only that there is sufficient risk to warrant the monitoring of events there and the implementation of preventive measures aimed at reducing that risk.Perhaps the most significant contributing factors to Kenya’s high risk of genocide are the strained and rivalry-prone social and cultural relationships between tribes, and the recent violent conflict in the aftermath of the December 2007 national elections. The country’s history is one of ethnic and political division, polarization and competition, which has largely contributed to a political and social order that promotes ethnocentrism and inter-tribal antagonism. This has led to violence in the past, as it did in late 2007 and early 2008 when the disputed election results led to mass violence between groups of political supporters, divided largely along ethnic lines, which killed as many as 1,500 and displacing hundreds of thousands.

The political and institutional responses to that violence may serve to mitigate Kenya’s risk of genocide. In 2008 the two primary presidential contenders, President Mwai Kibaki and Raila Odinga, agreed to share power in a coalition government. The agreement limited presidential authority primarily through the creation of a prime minister, a position that Odinga assumed while Kibaki remained president. In 2010 Kenya voted in favour of a new constitution that further decentralises power, both through the creation of a Senate as the second chamber of the legislature, and through the establishment of local counties and governors to whom some of the president’s executive powers were shifted. These developments seem to put Kenya on a positive trajectory toward democracy, limited government, and greater political representation and participation. But concerns remain about the government’s commitment to the reforms, the extent of their effects on Kenyan society and whether these changes may actually serve to exacerbate existing intertribal tensions.

The social and political divisions in Kenya are further complicated by the country’s economic situation. Poverty is rampant, unemployment is high, and economic inequality is significant and tends to correspond to ethnic divisions, leading to widespread competition for limited jobs and resources that inspires resentment amongst those who are unhappy with the outcome. Kenya’s bleak economic outlook contributes to a high risk of genocide particularly when seen in light of its young population. More than 40 percent of the country’s residents are below the age of 15, and three-quarters of the population falls between the ages of 15 and 29 years. When prospects for future employment, education or high social stature are so meagre, young people are more easily recruited into militias and gangs that offer prosperity, security, and a sense of purpose, often in the form of violent or criminal acts against a scapegoat group, like a rival tribe. This sort of recruitment becomes more and more likely when young people comprise such a large proportion of the country’s population.

The next national election is quickly approaching in December 2012, and it will be a test for those reforms made in the aftermath of the post-election violence of 2007-08. There are reports that tribal militias are engaged in an arms race in preparation for the elections, whether out of feelings of injustice, a sense of revenge, or anticipated self-defense and a mistrust of or lack of faith in state security forces. For these and other reasons the 2012 elections have potential to explode into mass violence on a scale much greater than that in 2007-08, and given the presence and combination of other structural indicators and risk factors, such violence may escalate into genocide.

This risk assessment represents the first step in the genocide early warning, risk reduction, and prevention process. The Sentinel Project’s next steps will include the following:

- Establishment of partnerships with civil society organisations working in Kenya to facilitate information sharing;

- Monitoring of ongoing events to identify genocidal processes that may be taking place;

- Assessments of whether any prominent Kenyan organisations – either state or non-state – or individuals harbour genocidal intent;

- Assessments of vulnerability to determine which – if any – ethnic groups in Kenya are the most likely to be targeted for genocide;

- Release of periodic threat assessments summarizing the information relevant to the above points; and

- Development and articulation of recommended preventive measures to be implemented by civil society and policy makers.