As the old saying goes, knowledge is power. Today, with the help of researcher Rachel Hatcher, the Sentinel Project team gained some expert knowledge on the history and context surrounding the Guatemalan genocide. Rachel is currently in Guatemala researching the ways in which the massacres are talked about today in the aftermath of the violence of the 1980s. On Sunday afternoon, she called in to share some of what she has learned through her research and empower us, as an audience, with her unique perspective. In preparation for the screening of Granito this coming Thursday, we now have an invaluable understanding of the difficult historical context of Guatemala depicted in the film.

As the old saying goes, knowledge is power. Today, with the help of researcher Rachel Hatcher, the Sentinel Project team gained some expert knowledge on the history and context surrounding the Guatemalan genocide. Rachel is currently in Guatemala researching the ways in which the massacres are talked about today in the aftermath of the violence of the 1980s. On Sunday afternoon, she called in to share some of what she has learned through her research and empower us, as an audience, with her unique perspective. In preparation for the screening of Granito this coming Thursday, we now have an invaluable understanding of the difficult historical context of Guatemala depicted in the film.

Rachel began her discussion by describing the cultural distribution across Guatemala. Despite most of the population belonging to one of the twenty-two groups of the Maya people, the Ladinos, a minority ethnic group, have traditionally held political, social, and economic power. It is no coincidence that the areas most affected by the violence during the genocide were regions like Quiche and Huehuetango, rural highland indigenous communities that many of the Maya people call home. It is in these areas that military forces under Lucas Garcia forced men and boys to patrol villages to “protect” themselves against guerrilla attacks, leading to what Rachel described as “neighbours killing neighbours” – this forced “patrolling” often resulted in the Mayan men and boys killing fellow Mayans. Rachel explained that this tortuous strategy of using Maya people as weapons against each other had the effects of increasing the numbers of military forces and also made mass killings more efficient and shifted direct accountability away from those in political power. These forced Maya recruits received training from the oppressive authoritarian regime that was damaging not only physically but also culturally and ideologically. Under constant threat of death, these recruits were forbidden from speaking any of their indigenous languages and were told that their cultures were inferior. At the end of the genocide, Hatcher noted that about one million men and boys had become forced recruits, and were responsible for some of the most infamous crimes throughout the genocide.

Although the years between 1978 and 1983 are generally recognized as the period of the genocide, internal armed conflict has been a feature of life in these areas of Guatemala since 1960 due to social exclusion, racism, and land conflict, as well as cultural revolutions such as the Democratic Spring. However, it is during those six years that the regime of Lucas Garcia, in power from 1978 to 1982, and Rios Montt from 1982 to 1983, attacked the Maya people. It is now acknowledged, according to Hatcher, that the army is responsible for about 90 percent of human rights violations, the guerrilla forces account for about 3-4 percent, while those responsible for the remainder are unknown.

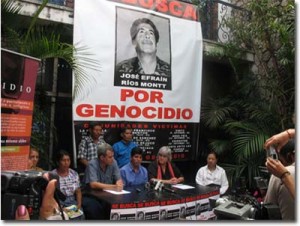

Today, political, social and cultural groups have banded together to demand that the political authorities responsible for these atrocities do not enjoy lifelong impunity. Currently, Rios Montt, former President of Guatemala, will stand trial for crimes against humanity inflicted on people in the Quiche region during the period in which he was head of state. Other crimes, however, such as the more subtle offenses of forced disappearance, are much more difficult to persecute, though many civil associations seek to punish those responsible. Further, forensic anthropologists, much like the one depicted in the film, have been working on a DNA database to identify bodies found through exhumations of mass graves. Though some believe that it would be more beneficial for Guatemalans to forget their sordid past and focus on current and future issues, many human rights advocates believe that Guatemala cannot go forward without addressing the many mistakes of the past.

Many thanks to Rachel Hatcher who provided us with this information. Granito: How to Nail a Dictator will now not only be a compelling film, but also a visual counterpart to the historical context we are now aware of.