By Barnabas Samuel, Sebit Martin, and Christopher Tuckwood

————————————————–

A critical part of starting any new initiative is for the Sentinel Project team to gather data about the local context and beneficiary population, which helps to inform project design and implementation. We did exactly that before launching the Hagiga Wahid project in Uganda together with our partners at the Community Development Centre (CDC) earlier this year. Project team members conducted a baseline survey of people living in the Rhino Camp refugee settlement and neighbouring communities near Arua in northwestern Uganda. The survey gave us important insights into the information needs and challenges of both South Sudanese refugees and Ugandan host community members as well as how these factors affect intercommunal tensions and their relationship to the conflict in South Sudan. This blog post outlines some of those findings.

Background information

Uganda is currently home to more than 1,310,000 refugees, of whom approximately 835,000 come from South Sudan, 365,000 from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and the remainder from other countries. Many of the South Sudanese refugees live in the Rhino Camp area, which is divided into six zones: Ocea, Siripi, Eden, Tika, Odubu, and Ofua. Originally established in 1980, Rhino Camp has expanded with the influx of refugees from recent conflicts and now also includes the Omugo Extension area, which is considered to effectively be the seventh zone, with Omugo overall now being the fourth largest refugee camp in Uganda. Upon arrival in Uganda, refugees are usually documented and given land, tools for homesteading, rights to work and travel, and access to education and other basic public services. However, despite the support provided to refugees, there are still gaps and numerous challenges with accessing healthcare, education, water, and fertile land that can support farming to improve livelihoods.

Security, conflict, and information risks

Refugees also face some degree of insecurity related both to the conflict back home in South Sudan and risks unique to life in Uganda. In terms of continuing impacts from the conflict, the interethnic nature of years of civil war means that some refugees have brought their hostilities and suspicions with them to Uganda. This situation is compounded by the fact that some tribes, especially the Dinka and Nuer, live in different camps with little interaction, which helps to breed mutual suspicion and maintain hostility. There have also been reported cases of attacks by host community members against refugees, which are driven by competition over natural resources such as water, land, and firewood. Again, the general lack of interaction between refugees and host communities tends to breed mutual suspicion.

The majority of South Sudanese refugees in Rhino Camp are from the Equatoria region of South Sudan with many coming from Yei, a town close to the borders of DRC and Uganda which has been a major hotspot in the conflict. Conversations with these respondents revealed their feelings that rumours and misinformation have contributed greatly to the escalation of violence in the country. Many also indicated that this is likely to continue being a problem in Uganda as members of various tribes have brought their hostilities with them and continue to face many of the same information deficits that encourage rumours and misinformation to circulate. This situation is now complicated further as refugees are exposed to questionable and potentially alarming information both about events in South Sudan and in their new surroundings in Uganda.

Survey results

The Sentinel Project’s first steps in Rhino Camp were in 2017 when CDC assisted with reaching the refugee camp to observe the situation and talk with people about their challenges, especially with regard to conflict, security, and peacebuilding. This established the need for a misinformation management project like Hagiga Wahid but it wasn’t until late 2018 and early 2019 that a pilot project could be established in both South Sudan and Uganda once funding was provided by the International Development Research Centre, the Australian government, and the New Zealand government. Work began in earnest in November 2018 with interviews of a number of key informants, meetings with local stakeholders, focus group discussions, community meetings, and the start of the survey discussed here. The goal of this work overall was to understand the situation of the refugees in Rhino Camp and assess the problem of rumours and misinformation as well as to understand how people there access, think about, and share information.

The project team is now happy to share the results of this research, which was conducted in Ocea, Tika, Ofua, and Omugo zones covering 19 clusters / villages over an area of 150 square kilometres. These locations were selected based on their populations, geographical size, and ethnic diversity. The following summary of results only reflects a selected set of key questions, while the full results reflecting the more details overall survey will be released in the future.

- Sample demographics – The survey team strove to recruit a representative sample of respondents. There were a total of 416 of these, who broke down as follows.

-

- Gender – 43.3% men and 56.7% women

- Nationality – 80.6% South Sudanese, 17.7% Ugandan citizens, and 1.7% other nationalities

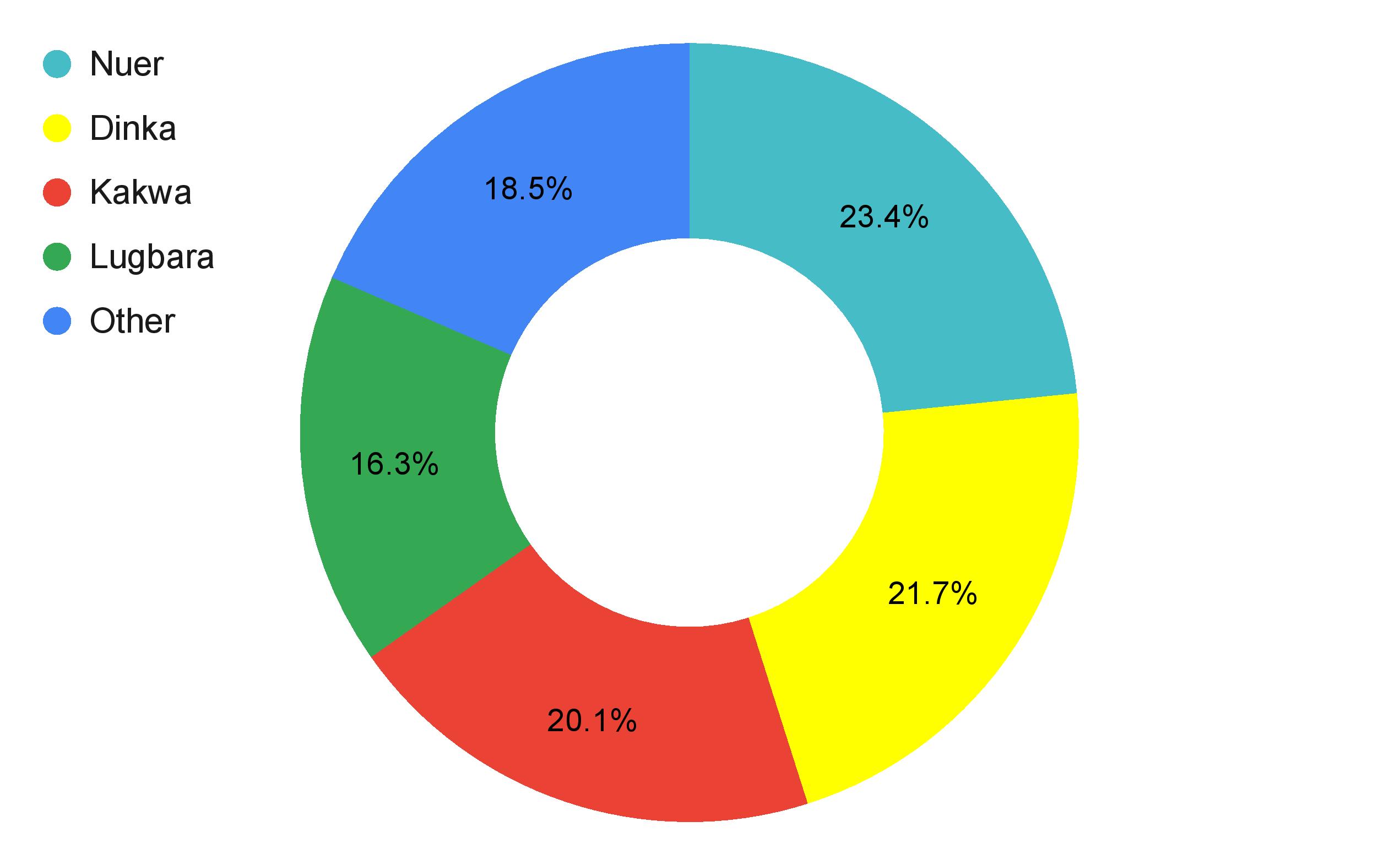

- Ethnicity – 23.4% Nuer, 21.7% Dinka, 20.1% Kakwa, 16.3% Lugbara, and 18.5% from other groups

-

-

-

- Religion – 95.5% Christian, 2.8% Muslim, and 1.7% reported other (or no) religious affiliations (This reflects South Sudan’s predominantly Christian population.)

- Household size – Average of 8 people per household

- Age – This was recorded in four different ranges with 28.1% being 15-25 years old, 38.9% being 26-35 years old, 22.4% being 36-49 years old, and 10.6% being 50 or more years old.

-

- Technology usage – It is important for the project team to understand what technology that respondents can access and how they prefer to send and receive information.

-

- Mobile ownership – Do you own a mobile phone?

-

- Yes – 61.9%

- No – 38.1%

-

- Communication methods – What is your preferred method of communication?

-

- Voice calls – 87.8%

- Facebook – 5.4%

- SMS – 4.1%

- WhatsApp – 2.7%

-

- Internet usage – Do you use the internet?

-

- Yes – 19.1%

- No – 80.9%

-

- Mobile ownership – Do you own a mobile phone?

-

- Information access and trust – Understanding how people access different types of information and the trust that they place in different sources is critical for effectively countering the spread of harmful rumours.

-

- Intercommunal information – Do you receive information about other ethnic or religious groups through different sources than your own?

-

- Yes – 37.4%

- No – 62.6%

-

- Trustworthy sources – Which source of information do you trust the most?

-

- Radio – 65.0%

- Phone – 15.0%

- Family – 4.0%

- Direct interaction – 3.6%

- Local leaders – 2.4%

- Other – 10%

-

- Trust (within groups) – How much do you trust information that you receive from members of your own ethnic or religious group?

-

- Highly – 43.7%

- Moderately – 47.0%

- Not at all – 9.3%

-

- Trust (between groups) – How much do you trust information that you receive from members of other ethnic or religious groups?

-

- Highly – 3.6%

- Moderately – 60.8%

- Not at all – 35.6%

-

- Intercommunal information – Do you receive information about other ethnic or religious groups through different sources than your own?

-

- Rumours and verification – Understanding how much that people hear rumours, act to verify them, and view their impacts is also critical for a project like Hagiga Wahid to be successful.

-

- Rumour incidence – Have you heard any rumours in the past 12 months?

-

- Yes – 58.4%

- No – 41.6%

-

- Fact checking – If yes, did you take any action to check if it was true?

-

- Yes – 41.5%

- No – 58.5%

-

- Rumours and violence – How much do you believe that rumours have contributed to violence and instability?

-

- Strongly – 73.6%

- Moderately – 22.1%

- Not at all – 4.3%

-

- Rumour incidence – Have you heard any rumours in the past 12 months?

-

Analysis

Golo, a refugee living in Tika, told the project team that “What we lack here exactly is the true source of information.” This aligns with the survey results, which show that refugees in Rhino Camp generally lack information and have little or no access to news, especially on local-level issues. This is particularly alarming in light of the fact that 73.6% of respondents believe that rumours strongly contribute to violence and instability. There are also several other interesting insights here.

Trust and accessibility – Radio is clearly the most trusted source of information among respondents, though few people actually own one compared to mobile phones, which 61.9% of people reported owning. This, together with the general preference for communicating using voice calls, as opposed to SMS and other text-based means of communication, may be related to the low level of literacy among respondents, which needs to be investigated further. Regardless of the cause, this set of preferences has clear implications for a mobile phone-based project such as Hagiga Wahid, though the lack of community radio stations serving the refugee audience is a challenging gap to fill and requires a sustained focus on mobile phone-based channels for at least the immediate future.

Rumour prevalence – The problem of rumours and misinformation is also substantiated by the survey results, which show rumours as being very common in the camps with 58.4% of respondents reporting that they heard a rumour over the previous 12 months. Considering the time frame, this number may actually appear to be low and could reflect different views among respondents of what constitutes a rumour, which needs to be investigated further.

Verification – Rumour verification is clearly another weak area, with the majority of respondents (58.5%) saying that they have not taken action to check if rumours are true. This may at least partially reflect the lack of means to do so, as reported by a woman in Katiku Cluster in Ocea Zone, who explained that “We only hear rumours that something has happened somewhere like in South Sudan, a village, or in the (other) camp but whether this is true or false, we don’t know… this can sometimes trouble us.”

Information confidence – The survey results show a clear gap in how respondents assessed their own confidence in access to information about different geographical areas. As might be expected, most respondents felt either well informed or moderately informed about their own villages or clusters since they live in small localized communities. However, the level of information confidence drops off significantly when moving beyond the village / cluster level, with approximately 10% or fewer people saying that they feel well-informed about the zone / district level, areas outside of the camps, and South Sudan. Most notably, nearly half of all respondents reported being not at all informed about the situation outside of the refugee camps and more than half said that they were not at all informed about the situation in South Sudan. Such information deficits have clear potential to both impact relations between refugees and host communities and well as refugee decisions on matters such as returning home.

|

Well Informed |

Moderately Informed |

Not At All Informed |

|

| Village / Cluster |

29.6% |

50.2% |

20.2% |

| Zone / District |

10.0% |

58.7% |

31.3% |

| Outside Camps |

7.1% |

46.1% |

46.8% |

| South Sudan |

10.4% |

36.4% |

53.2% |

Ethnicity-based trust – An interesting aspect explained by some respondents is that even when people do not know whether a rumour is true, they tend to take them seriously and often believe them to be true, in turn telling other people about them, though some recognize that this is likely to further distort and exaggerate the report. This belief in the truth of rumours may sometimes be influenced by the nature of the person reporting them, even if the original source is not known. Ethnicity plays a large role here with the survey results indicating that 43.7% of respondents highly trust information received from members of their own ethnic group while only 3.6% highly trust information received from members of other ethnic groups and 35.6% do not trust it at all.

Clearly, there is an opportunity for Hagiga Wahid to help bridge information gaps and ethnic divides which erode intercommunal trust. In the long term, this will contribute to improved information access, peace, stability, and development for both refugees and host communities.