Community farm field in Masisi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

![]()

![]()

Gender equity has always been a crucial aspect of the Sentinel Project’s work. This is demonstrated well by misinformation management projects, in which engaging both men and women is essential due to their complementarity in conflict information ecosystems. In addition to being disproportionately affected by gender-based violence, women face structural barriers to accessing reliable information as well as development and humanitarian programming. Rumours and misinformation (including disinformation) pose a challenge to development, governance, public health, and human security efforts worldwide, especially in places where people face serious information deficits. These issues particularly have the potential to affect marginalised populations more than others. Women, girls, and members of LGBTQ2S+ communities are frequent targets of this kind of harmful content as well as physical violence, especially when they are members of ethnic, religious, or other minority communities. Therefore, vulnerable groups have the most to gain from a system that can circumvent many social, cultural, political, and structural barriers preventing them from accessing reliable information, making accessibility and inclusivity high priorities for the Sentinel Project’s overall violence prevention mission. The 2030 Agenda for the developed 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) commits the international community to advocate for peaceful and inclusive societies that support national development priorities. Over 36 targets across the UN 2030 Agenda are directly related to peace, justice, or inclusivity. The Peacebuilding Fund’s investment in the Sustainable Development Goals goes beyond the objective of SDG 16, which is the most intuitively linked to sustaining peace. Working towards gender equity is not only the right thing to do. It also makes the Sentinel Project’s overall work more effective.

As we move towards the end of Women’s History Month, a growing topic of concern worldwide is the link between gendered misinformation and violence against women. Most research on gender and misinformation is related to women in politics since many disinformation campaigns seek to tarnish their reputations and distract from their expertise and politics. Misogynistic rumours often target women who are active in the public sphere as opposed to women in general. A study conducted by Pollicy in 2021 found that the violence targeting women politicians in Uganda, was based on their perceived inability to uphold patriarchal cultural norms, while attacks against their male counterparts were based on their ability to perform in leadership roles. Looking beyond the political realm, there is a dearth of information about how sexism and gender biases may pervade rumours, misinformation, and hate speech in conflict zones. Our understanding is that, together, these phenomena can lead to offline violence and mass atrocities, particularly in already volatile environments. As communications technology has become more widely distributed in lower-income countries, the spread of inaccurate, incomplete, or fabricated information is an increasingly significant threat to peace and stability, particularly in regions with limited access to reliable third-party media. The Sentinel Project’s three flagship misinformation management projects in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Kenya, and South Sudan play a role in mitigating rumours and providing accurate information and context back to the community. Named Kijiji Cha Amani (Swahili for “Peace Village”), Una Hakika (Swahili for “Are you sure?”), and Hagiga Wahid (Juba Arabic for “One Truth”), respectively, these projects can reduce the risk of offline conflict and violence. Misinformation management systems cannot be imposed from above. Instead, they must be implemented by entering into communities using culturally relevant introduction processes followed by cooperative efforts. Women have the opportunity here to act as peacebuilders in their respective communities due to their unique roles in households, organisations, and livelihood groups. This potential is especially salient when it comes to monitoring, verifying, and countering the spread of harmful rumours and misinformation since women often interact in different types of information-sharing networks than men do.

John Green Otunga, our East Africa program manager, reflects on his extensive experience in engaging with women groups in Kenya:

Previously, women played a huge role in fueling the violence by inciting the men in society. They used to compose songs that promoted violence and praised their heroic acts. It is the same women that we now work with to pass on peace messages and encourage peaceful co-existence. Most women are caregivers and remain at home most of the time. They have sufficient information about what is happening in their local areas and often meet at the markets and access information. Thus, we have worked with these groups that enable us to tap into many key information networks.

Una Hakika (Kenya)

There is strong evidence that the Una Hakika project in Kenya increased women’s access to information and afforded them the ability to bypass traditional (including patriarchal) authority structures and information pathways. The Sentinel Project’s previous work on election violence prevention in Kenya helped us to understand the national and local political context, including women’s role in government. At the outset of the Una Hakika project in early 2014, our initial field surveys documented that women were, on average, 8.7% less likely than men to report feeling well informed about events at the local, county, and national levels. By the time of the next survey in September 2015, women who had previously reported having access to no information or a moderate level of information showed respective improvements at rates twelve (12) and six (6) times greater than the improvements shown for men. The gap between the genders had also shrunk drastically. These results were not obtained easily. Though infrequent, there were instances where the tension between specific communities was too high to guarantee the safety of participants or where introducing members of another ethnic group to a particular community was deemed too disruptive to be beneficial. In 2017, Kenyan women candidates faced targeted gendered violence. Elections also increased the risk of GBV for the general female population. For example, in some of Nairobi’s slums during the 2017 general elections we received reports from women that police officers had allegedly abused them. In Tana River, some women provided sensitive information that enabled us to pre-empt potential attacks from those who heard their men’s plans to attack a particular village. Recognizing the above, our project team actively recruited women into its programming, making them especially attuned to any rumours or misinformation related to women’s safety and engaging accordingly.

Prevention of violence under SDG 10 means seeking inclusive solutions through dialogue, institutional reform, and policies formulated through a participatory process and responding to the needs of different parts of society equitably. Since then, we have created an exclusive network for women from affected communities to seek inclusive solutions through dialogue, organised capacity-building training on peacebuilding, misinformation management, and access to vital information. Una Hakika has also provided a reporting mechanism for women who are otherwise hesitant to share information on human rights violations and gender-based violence with relevant authorities and humanitarian organisations for intervention.

Rumours related to women and girls

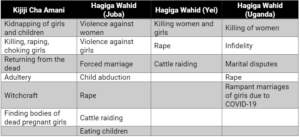

The table below outlines the results of baseline surveys that we conducted in three countries where we work – DRC, South Sudan, and Uganda – all of which have long been affected by violence and currently present vital opportunities to ensure equitable participation in community-led peace initiatives. We asked respondents about the rumours that they had heard related to women and girls and they provided examples that are predominantly associated with the following themes.

We also learned that 39% to 43% of respondents across the four locations have passed on rumours related to women and girls without first checking whether or not they were true. These findings are not surprising because similar percentages of respondents stated they had also passed on rumours related to violent conflict more generally without first verifying them. For example, Hagiga Wahid has encountered GBV-related rumours, such as those about alleged rapes, that evoked emotional responses from community members. A rumour from 2019 involved a woman who was accused of poisoning people. She was rumoured to be killed by family and friends of the allegedly poisoned children and elders. The rumour of the murder was proved to be true.

Access to literacy information in Hagiga Wahid (South Sudan)

SDG 4 on education includes references to discrimination in education, education on human rights and gender equality, and promoting a culture of peace and nonviolence. The Hagiga Wahid initiative works towards socioeconomic sustainability by encouraging long-term behavioural changes that build a culture of critical thinking, fact-checking, and information literacy, contributing to peace and stability. By introducing a system by which communities could submit reports to receive verified information and training community ambassadors to independently and sustainably verify information, Hagiga Wahid has catalysed significant improvements that participants reported. More than half of the community ambassadors from Yei county have been trained so far (9 out of 17) are women for this project. Women responding to our baseline survey were far more likely to report feeling they lacked the tools and training to verify the information. Only 36.4% answered in the affirmative during the initial survey, compared with 49.0% for men. However, by the end of the project cycle, near parity had been reached as men and women reported being confident in their ability to verify information, with 77.6% and 75.8%, respectively, responding in the affirmative.

Community ambassadors in Yei, South Sudan

Gender justice in peacebuilding also means much more than overcoming barriers to participation in what will continue to be oppressive power structures. A feminist approach is crucial in shifting and transforming power since it endeavours to understand how power and might are designed and used. SDG 16 supports peace and strengthening institutions. A feminist framework is radical because it challenges our current understanding of conflict and conflict resolution for the greater good. Yuriko Cowper-Smith, the Sentinel project’s research and engagement officer, points out that:

Although conflict is intersectional (it affects people of various backgrounds and genders in distinct ways), women and girls have consistently been excluded from or sidelined during formal and informal peacemaking conversations. Equitable participation at all levels of peacemaking in a given community, state, region, and country should be a goal. Not only would this ensure better representation, but the presence of a spectrum of people with different experiences will enrich how conflict is dealt with – digging deep into the root causes of violence.

Kijiji Cha Amani (DRC)

Empowering women as active peacebuilders is vital for ensuring effective solutions to conflict. SDG 5 on gender equality aims to eliminate violence against women and girls and ensure their full and effective participation in society. Women have unique collaborative approaches that engage communities and leaders through resources and capacity building. They also have different incentives to report and counter rumours. The recent focus group discussions organised by our community ambassadors in Masisi village resulted in creating a community field to consolidate peace between its members from different tribes. Most of their conflicts often stemmed from prejudices, stereotypes, hate speech towards other tribes, rumours, and land disputes. The women farm potatoes and meet regularly to discuss strategies for reducing community violence.

Potato farming in Masisi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Lea Mastaki, one of our Kijiji Cha Amani project coordinators, working towards social cohesion remarks that:

Every Sunday, we meet to discuss the issue of peace, security. Each mother or woman comes with information or rumours from her neighbourhood. We gather this information and then present it to the competent authorities. Since rumours and misinformation are often at the root of conflicts in our province, we talk about it every time we meet. Kijiji Cha Amani sensitised a group of women from 18 districts of Goma; the result is that all these women were happy to know about Kijiji Cha Amani and its achievements.

Women have a unique role to play in peacebuilding and misinformation management efforts due to the positions they occupy within their families and communities. As they can identify otherwise overlooked conflict drivers, women’s inclusion leads to the formulation of more effective prevention mechanisms, which is why it remains central to the Sentinel Project’s commitment to harnessing women’s great potential in peacebuilding. Preventing violence requires departing from traditional economic and social policies when risks are increasing. It also means seeking inclusive solutions through dialogue, adapted macroeconomic policies, institutional reforms, and policies that increase inclusion. By bringing attention to gender representation in peacebuilding, it is possible to reverse the degree to which women are more greatly affected by conflict through increased participation.

References

Ali, N.M., (2011). “Gender and State building in South Sudan,” The United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved on March 02 2021 from https://www.peacewomen.org/assets/file/SecurityCouncilMonitor/Missions/SouthSudan/special_report_usip_december_2011.pdf

Oxfam. South Sudan Gender Analysis. (2016). Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620207/rr-south-sudan-gender-analysis-060317-en.pdf?sequence=1

Peacebuilding Fund Investment in the Sustainable Development Goals (2019) from https://www.un.org/peacebuilding/sites/www.un.org.peacebuilding/files/documents/1907427-e-pbf-investments-in-sdgs-web.pdf

Amplified Abuse: Report on Online Violence Against Women in the 2021 Uganda General Election (2021) from https://archive.pollicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Amplified-Abuse-Report.pdf